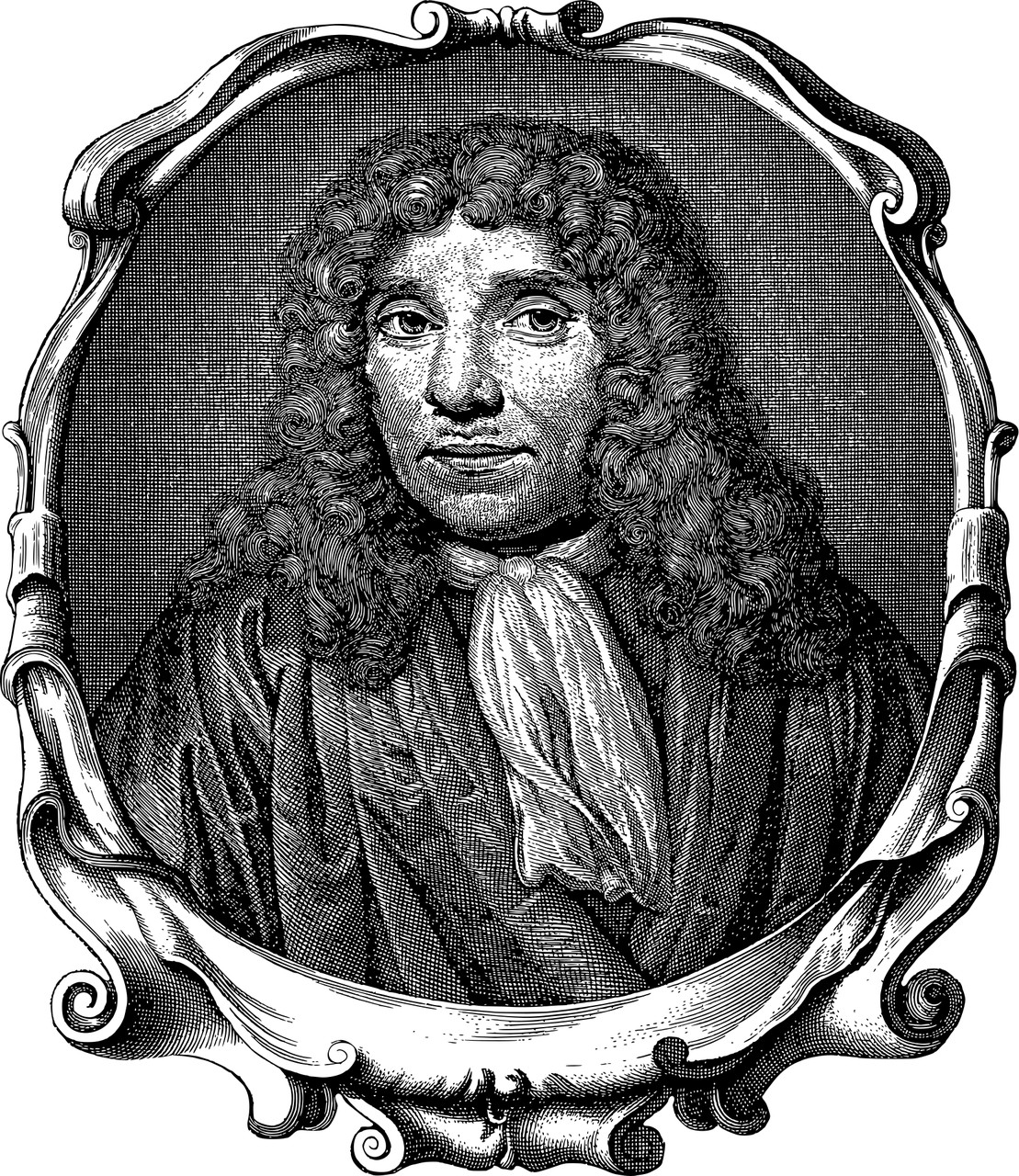

Father of Microbiology

Image courtesy of pixabay.com

Antony van Leeuwenhoek, a Dutch linen-draper, set the scientific world on a totally new course when he discovered bacteria and animal processes that discredited a common theory of the time, spontaneous generation.

We all did it. Sometime during our junior high school science class, the microscope came out and glass slides were created with ordinary pond water sandwiched in between the slide and the thin glass cover. What, exactly, we saw was determined by the sample, but without a doubt, protozoan and algal specimens were involved. We knew what we would observe because we could see images in our textbooks. These microscopic creatures were cool, but not shocking.

That was not always the case. Until about 1657, no one had ever observed these tiny creatures. That is, until a linen merchant named Antony (Antonie) van Leeuwenhoek stepped into the picture.

Van Leeuwenhoek was born in 1632 in Delft, the Netherlands. His life was destined to be one of extreme ordinariness. Son of a basket maker, his father died early in Antony’s life. At 16, Antony left for Amsterdam to learn the trade of linen-draper (a dry-goods merchant specializing in linens). Making a living was on his mind and university was not even a consideration. He eventually made his way home, started a linen business and married. His life was as vanilla as a life could be. Except for one thing—Leeuwenhoek, was curious. Six years before his death at age 90, while thanking the University of Louvain for sending him a medal designed in honor of his research, he said, “[M]y work, which I’ve done for a long time, was not pursued in order to gain the praise I now enjoy, but chiefly from a craving after knowledge, which I notice resides in me more than in most other men.” And indeed, it did.

A quality magnifying lens was necessary for his business inspecting linens and he acquired one in 1653. This developed into an interest in grinding and polishing his own lenses. In his lifetime, he ground over 500, most of them very small, some as small as the head of a pin. These he would fasten to small brass plates, add a focuser and a specimen holder, and have a serviceable microscope. His lenses, many of which are museum pieces today, had magnifications from 50 to 300 power (my favorite hand lens is 10 power or 10X). His lenses were unique and he never taught anyone how to make them (he was afraid that if he taught one person he would have to teach everyone and thus lose much time he wanted to devote to investigations). Even today, science has not been able to duplicate what he built.

Courtesy Florida State University

It was not just the apparatus though, that brought him eventual fame and even membership in the Royal Society of London, something unheard of for a layman who did not speak English or Latin. Inspired by Robert Hooke’s book, Micrographia, he began to indulge his curiosity and explore the world beyond unaided sight and his discoveries astounded the world.

Around 1674 he became the first person to see and describe those crazy protozoans we all saw in Junior High and what Leeuwenhoek called, “animalcules.” A few years later, he described the first bacteria, even accurately estimating their size: “so small in my eye that I judged, that if 100 of them lay [stretched out] one by another, they would not equal the length of a grain of course Sand.” His descriptions were so wild that the Royal Society refused to believe him until he challenged them to confirm his discoveries, which they did.

His study of ants, fleas, mussels, and even eels changed the thinking of science. At the time, these critters were all thought to spontaneously generate from non-living matter. This theory conveniently explained how maggots could suddenly appear in decaying flesh, how eels were produced from dew, and fleas and mussels from grains of sand. With careful observation, Leeuwenhoek demonstrated that all animals followed “a regular course of generation,” debunking the spontaneous generation theory.

Over the course of 50 years, Antony van Leeuwenhoek, uneducated, but a profoundly curious and meticulous amateur naturalist, contributed 375 publications to the Royal Society of London’s journal, Philosophical Transactions. Besides building his own proprietary microscopes and discovering protozoa and bacteria and repudiating spontaneous generation, he was the first to describe spermatozoa, red blood cells, the inner workings of cells, muscle striations, plant micro-biology, and parthenogenesis (development of an unfertilized egg) in fleas. Because of his work, he is recognized today as the father of Microbiology.

“I've spent more time than many will believe [making microscopic observations], but I've done them with joy, and I've taken no notice those who have said why take so much trouble and what good is it?” Antony van Leeuwenhoek.

Help Idaho Wildlife

When we traveled across the state in October 2017, we visited most of the Idaho Department of Fish and Game wildlife management areas. Most of the vehicles we saw using the wildlife management areas did not have wildlife plates. Buying wildlife plates is a great way for non-hunters and hunters alike to support wildlife-based recreation like birding.

C'mon folks, let's help Idaho's wildlife by proudly buying and displaying a wildlife license plate on each of our vehicles!

See below for information on Idaho plates. Most states have wildlife plates so if you live outside Idaho, check with your state's wildlife department or vehicle licensing division for availability of state wildlife plates where you live.

And tell them that you heard about it from Nature-track.com!

Wildlife License Plates

Great news! as of 2024, there are three NEW designs for license plates. They still are bluebird, cutthroat trout and elk, but they are beautiful.

Idaho Wildlife license plates provide essential funding that benefits the great diversity of native plants and wildlife that are not hunted, fished or trapped—over 10,000 species or 98% of Idaho’s species diversity. Game species that share the same habitats (such as elk, deer, antelope, sage-grouse, salmon, trout) also benefit from these specialty plates.

No state tax dollars are provided for wildlife diversity, conservation education and recreation programs. Neither are any revenues from the sale of hunting or fishing licenses spent on nongame species. Instead, these species depend on direct donations, federal grants, fundraising initiatives—and the Idaho Wildlife license plates.

Both my vehicles have Bluebird Plates. I prefer the bluebird because the nongame program gets 70 percent of the money from bluebird plates, but only 60 percent of the money from elk and trout plates - 10 percent of the money from elk plates supports wildlife disease monitoring and testing programs (to benefit the livestock industry) and 10 percent from cutthroat plates supports non-motorized boat access.

Incidentally, in 2014, the Idaho Legislature denied the Department of Fish and Game the ability to add new plates or even to change the name of the elk and cutthroat plates (very specific) to wildlife and fish plates, a move that would have allowed for changing images occasionally and generating more revenue. It would seem that they believe that we Idahoans don't want a well funded wildlife program.

I think it is time we let the Legislature know that Idahoan support wildlife funding and that we would like to see these generic plates come to fruition.

"WOW. What a phenomenal piece you wrote. You are amazing." Jennifer Jackson

That is embarrassing, but actually a fairly typical response to my nature essays. Since The Best of Nature is created from the very best of 16 years of these nature essays published weekly in the Idaho Falls Post Register (online readership 70,000), it is a fine read. It covers a wide variety of topics including humorous glimpses of nature, philosophy, natural history, and conservation. Readers praise the style, breadth of subject matter and my ability to communicate complex and emotional topics in a relaxed and understandable manner.

Everyone can find something to love in this book. From teenagers to octogenarians, from the coffee shop to the school room, these nature essays are widely read and enjoyed.

Some of the essays here are my personal favorites, others seemed to strike a chord with readers. Most have an important message or lesson that will resonate with you. They are written with a goal to simultaneously entertain and educate about the wonderful workings of nature. Some will make you laugh out loud and others will bring a tear to the eye and warm your heart.

Readers Write:

"You hit a home run with your article on, Big Questions in Nature. It should be required reading for everyone who has lost touch with nature...great job!" Joe Chapman

"We enjoyed your column, Bloom Where Planted. Some of the best writing yet. The Post Register is fortunate to have your weekly columns." Lou Griffin.

To read more and to order a copy, click here or get the Kindle version

Copies are also available at:

Post Register

Island Park Builders Supply (upstairs)

Barnes and Noble in Idaho Falls

Harriman State Park, Island Park

Museum of Idaho

Valley Books, Jackson Wyoming

Avocet Corner Bookstore, Bear River National Wildlife Refuge, Brigham City, Utah

Craters of the Moon National Monument Bookstore, Arco, Idaho